A Digital Boom in a Thirsty City

Batam races to become Indonesia’s data hub, but at what cost to its water supply?

By: Rezza Aji Pratama

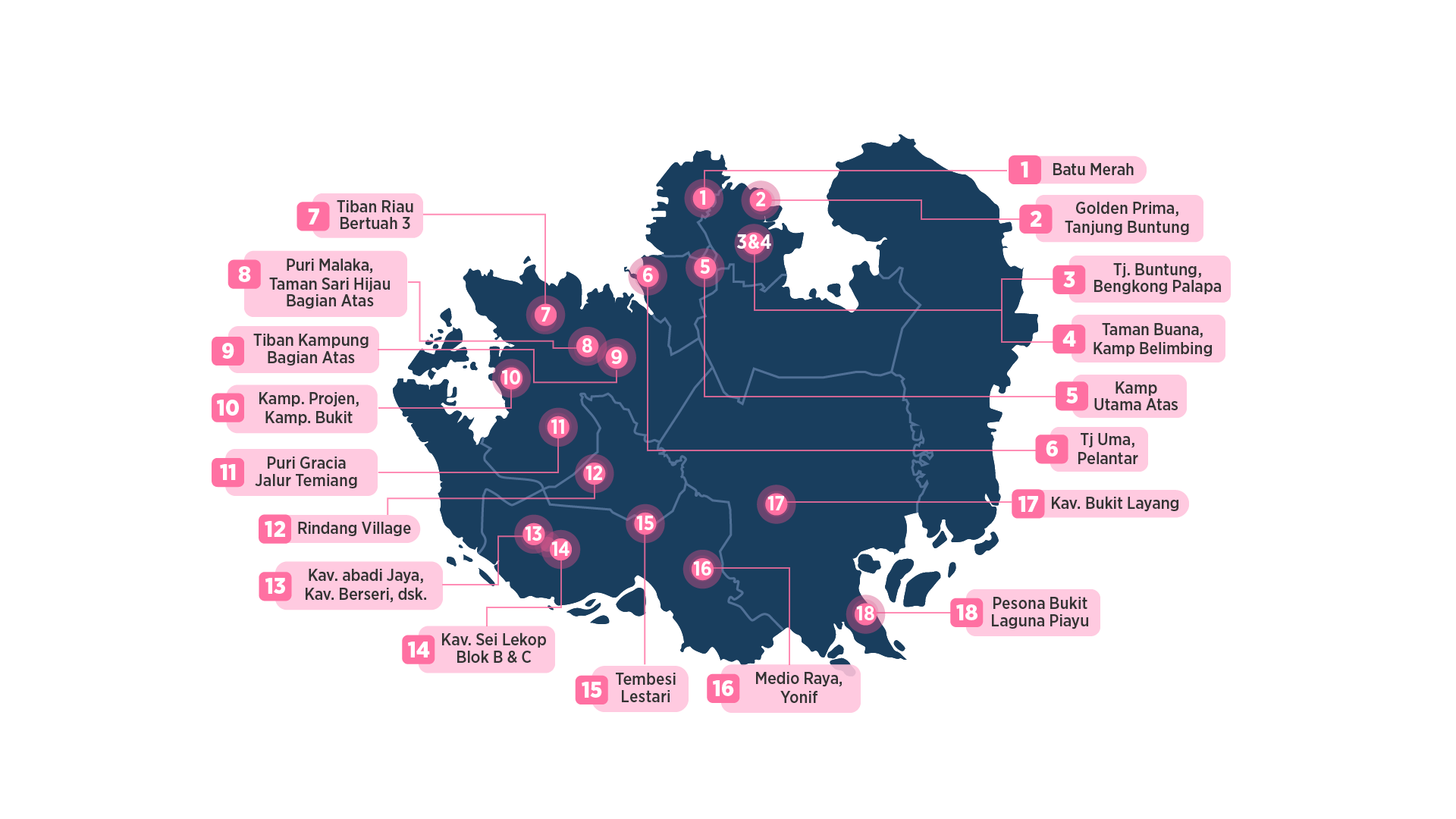

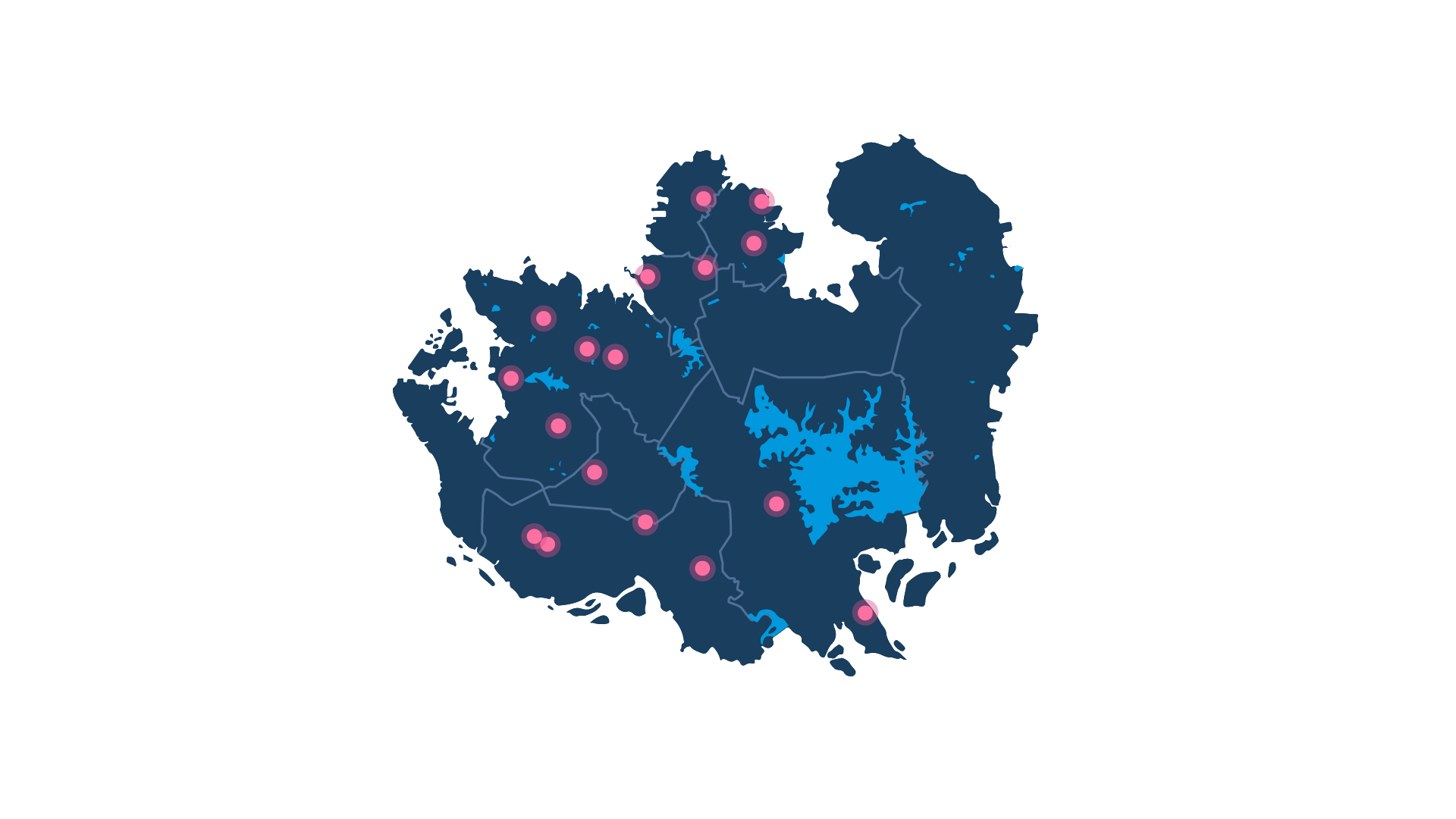

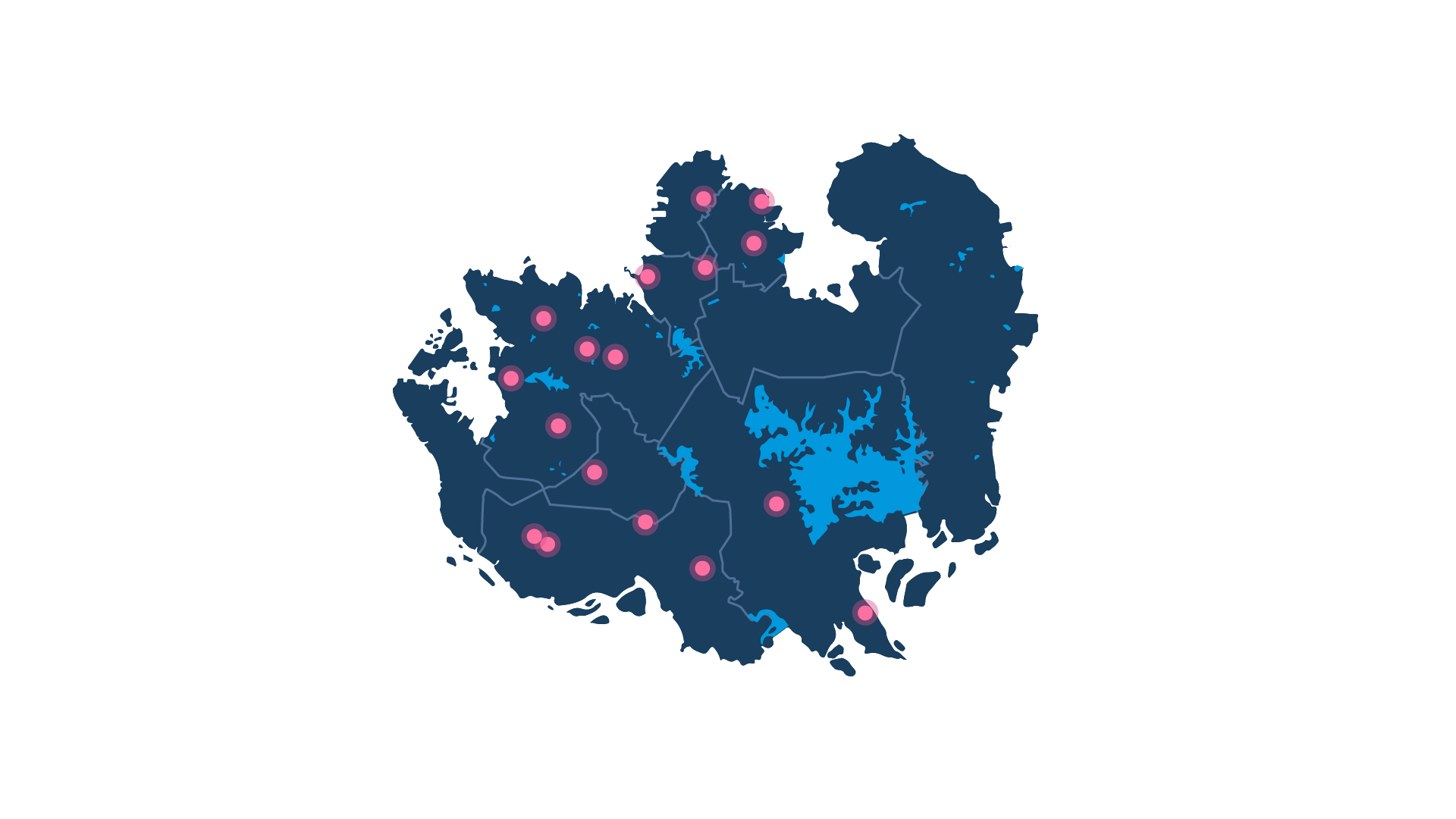

In Batam, an island city in western Indonesia that relies entirely on rainwater, a new race is underway—not for survival, but for servers. At least 18 data centers are being built here, each demanding millions of liters of fresh water every day.

At Kabil Industrial Park, a massive four-story structure is taking shape — one of three data center buildings planned for the site. Each floor covers an area roughly the size of a football field, bringing the total building space to over 26,000 square meters and accommodating around 1,500 server racks.

Once completed, the three windowless concrete blocks will have a combined capacity of 56 megawatts and could require up to 3 million liters of water per day for cooling. That amount of water is sufficient to meet the daily needs of approximately 30,000 people, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline of about 100 liters per person per day.

The $600 million project is owned by NeutraDC–Nxera, a joint venture backed by some of Southeast Asia’s biggest digital players. Telkom Indonesia through its subsidiary Telkom Data Ekosistem (60%), Singtel through Nxera (35%), and Medco Power Indonesia (5%).

“The first will go online in early 2026,” Indrama Purba, CEO of NeutraDC-Nxera Batam, told Katadata.

The site in Kabil Industrial Park is just one of several data center mega-projects planned across Batam. Data centers are the backbone of digital life. Every time you scroll through Instagram, watch YouTube, or send an email, your data travels through and is stored inside these facilities. Without them, there would be no internet. In the age of artificial intelligence (AI), the demand for data centers is greater than ever.

Yet, data centers are also among the thirstiest infrastructures of the digital age. David Mytton, a researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, estimates that a single megawatt (MW) of data center capacity consumes about 25.5 million liters of water per year for cooling alone.

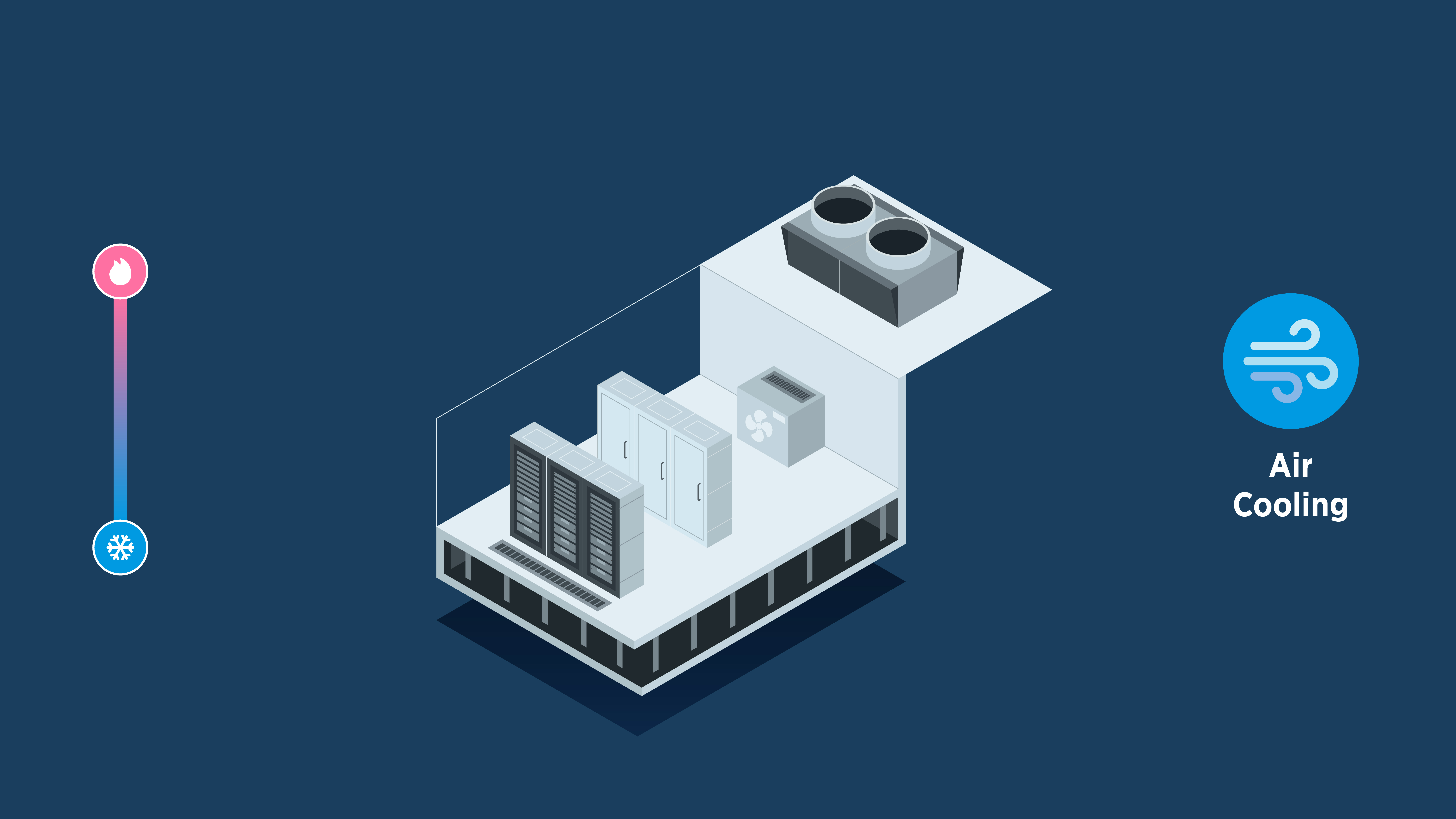

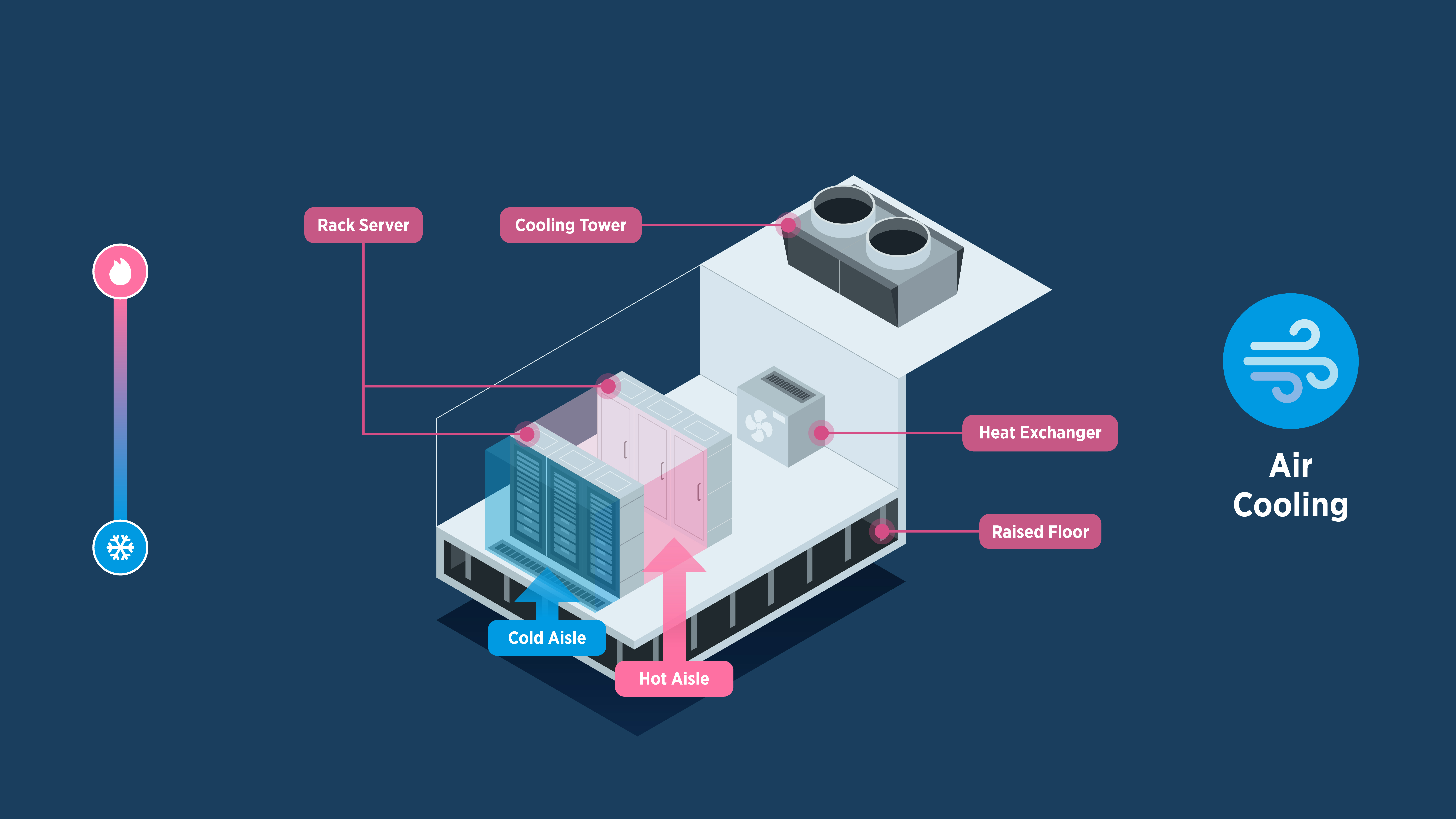

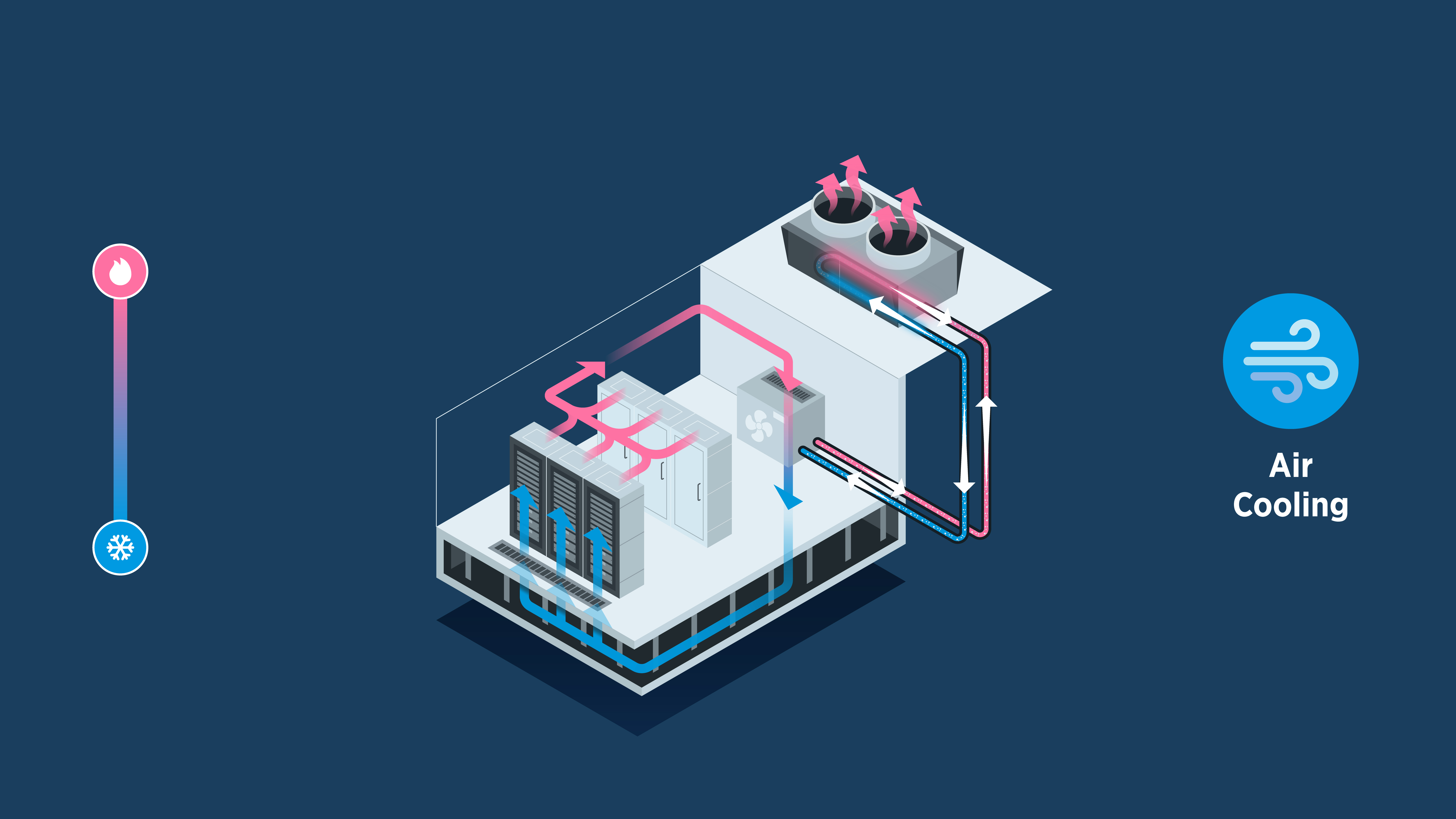

Inside these facilities are vast halls filled with rows of metal cabinets that hum with energy. Each cabinet houses servers, powerful computers that store and process our digital lives. These servers run non-stop, 24 hours a day. Like any engine, they generate enormous heat. If that heat isn’t removed quickly, the machines can overheat and fail within minutes.

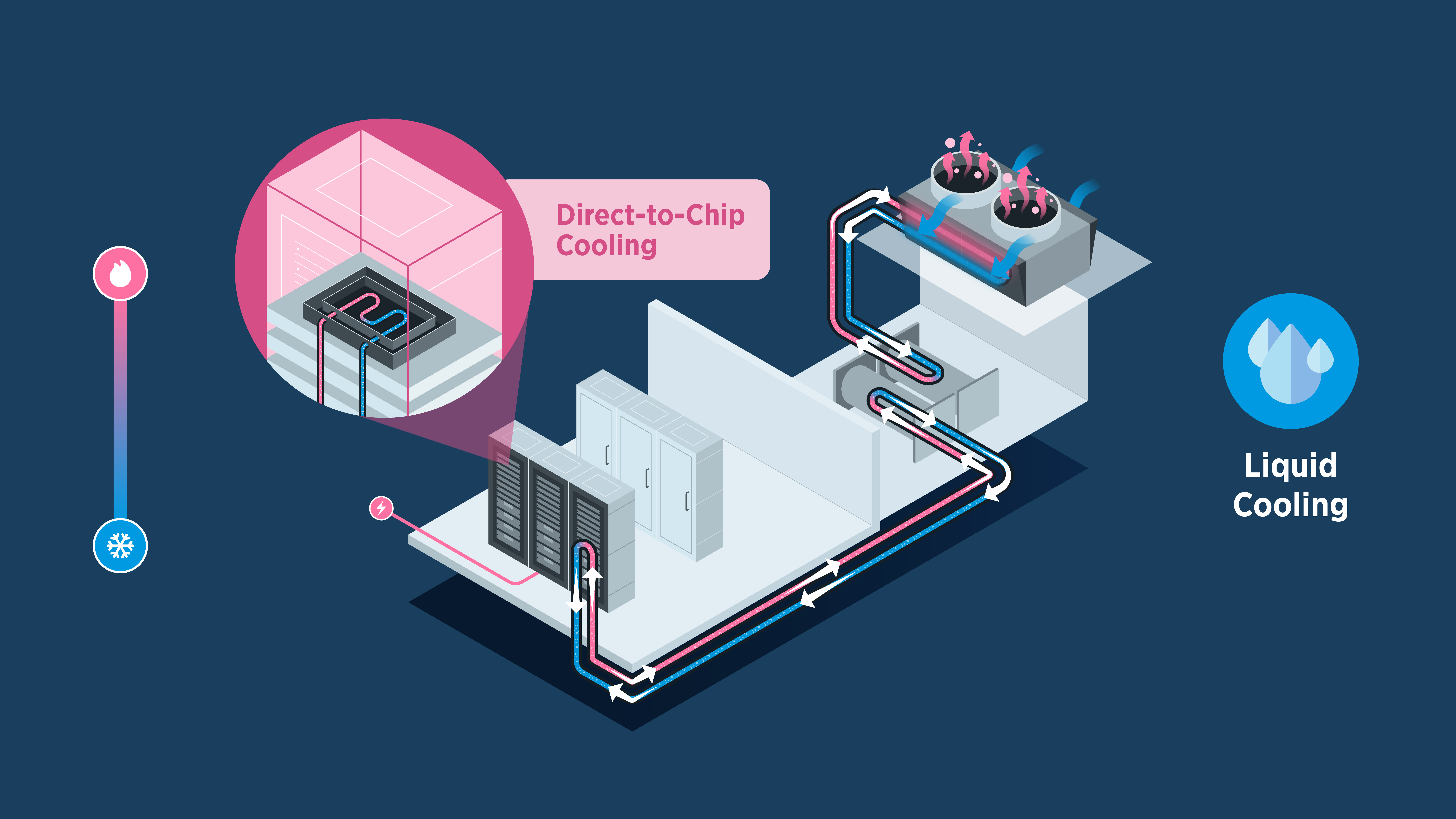

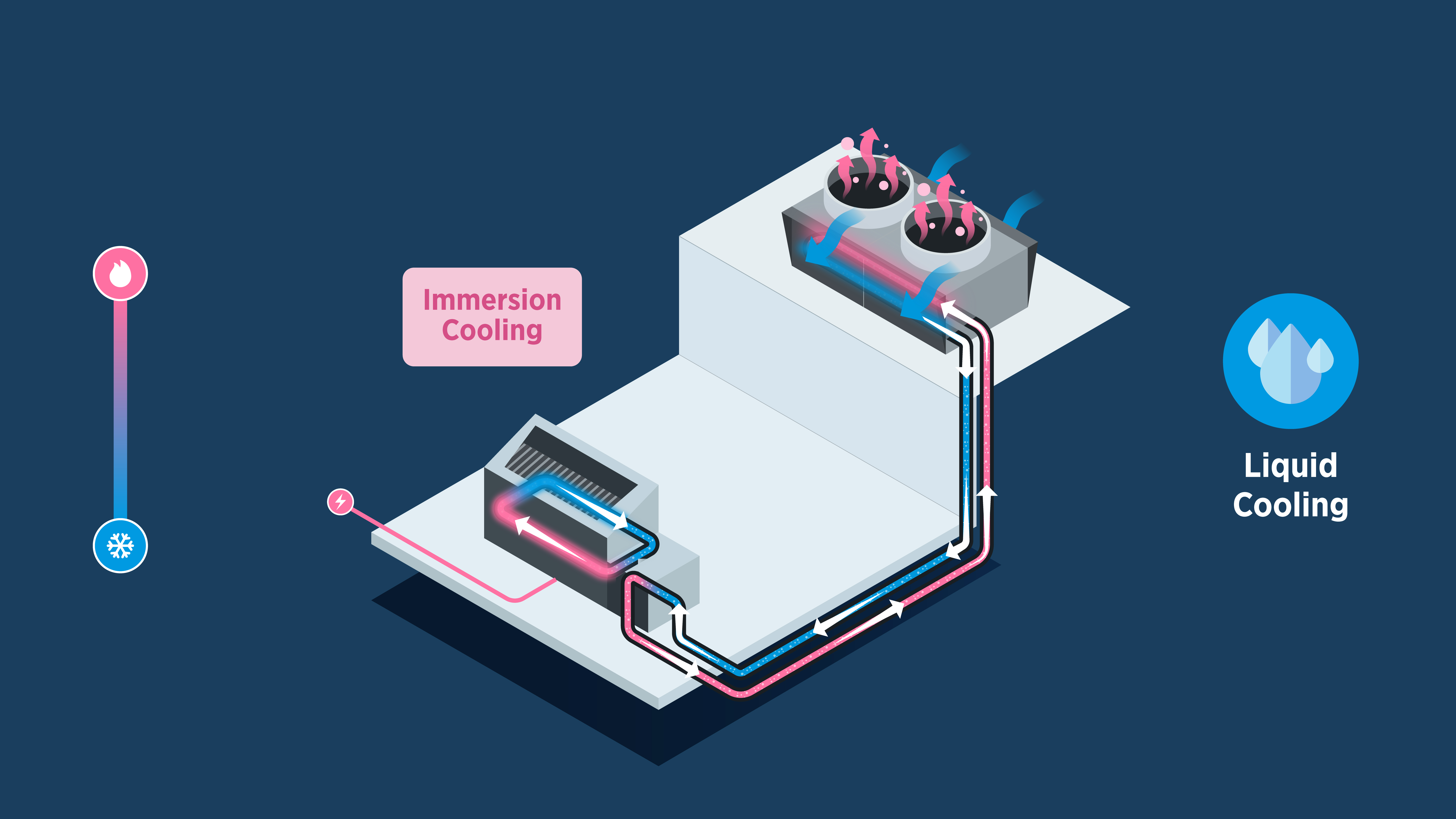

That’s why data centers consume so much water. Engineers deploy a range of cooling technologies. From massive air-conditioning units to advanced liquid-cooling systems, or sometimes a hybrid of both, to keep the servers cool enough for the internet to stay alive.

The growing appetite for digital infrastructure is fueling Southeast Asia’s data center boom. In 2024, the region’s data center construction market was valued at US$5.42 billion, and it is projected to climb to US$11.8 billion by 2030. The growth is driven by hyperscale operators, the rising demand for AI, edge computing, rapid digitalization, and the widespread shift to cloud-based services.

The air-cooling system uses a household-type air conditioner as the cooling unit. Hot air is absorbed by the cooling machine and then replaced with cold air.

The air-cooling system uses a household-type air conditioner as the cooling unit. Hot air is absorbed by the cooling machine and then replaced with cold air.

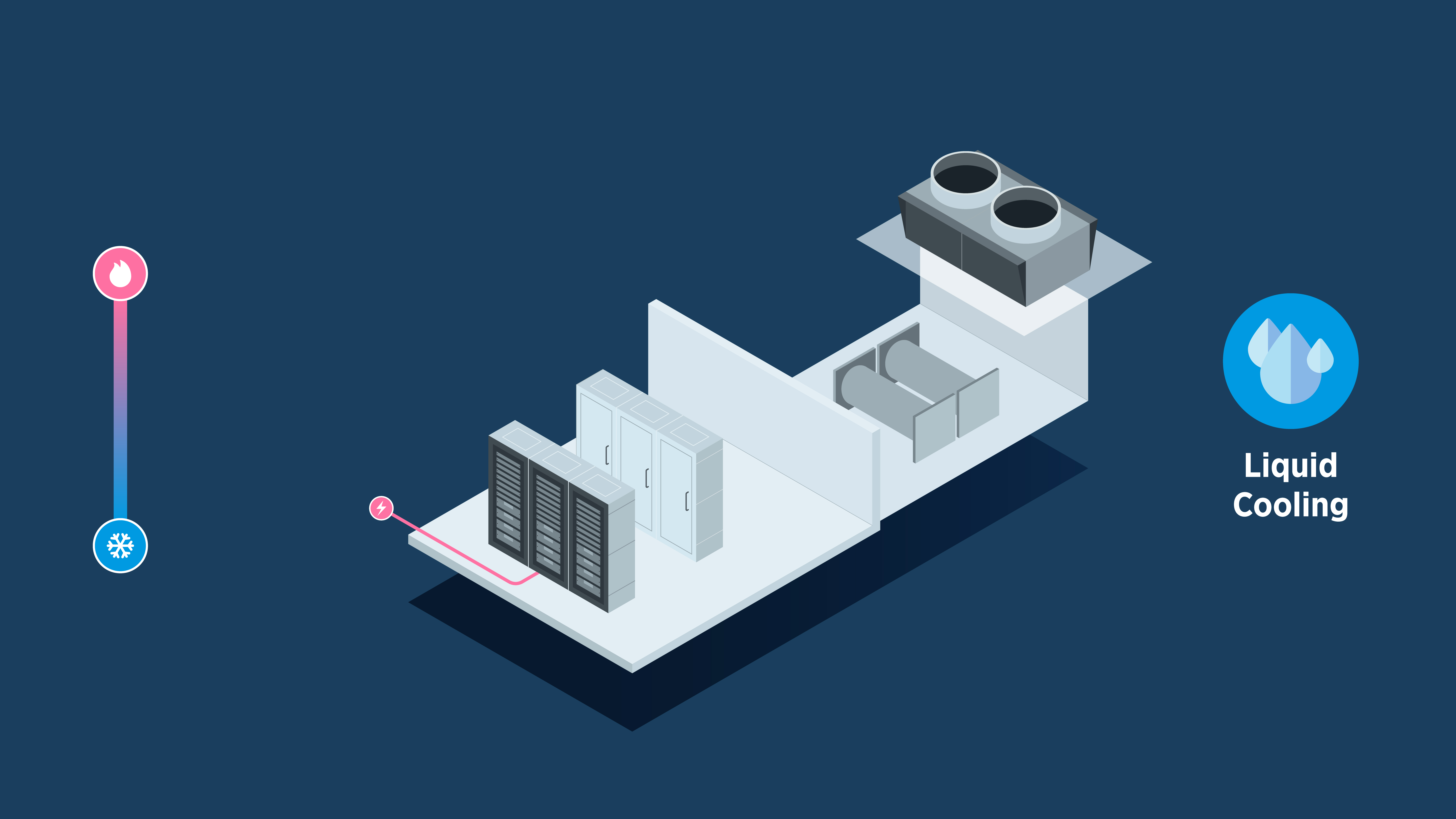

The liquid system uses a special coolant that is placed around the server racks.

There is also a direct-to-chip system that circulates cold liquid directly to the server chips.

In some data centers, they even immerse the servers in a liquid, a method known as immersion cooling.

Batam, which sits strategically along the Malacca Strait, is one of the data center epicenters in Southeast Asia. The island city, just 45 minutes by ferry from Singapore, has long drawn waves of investment eager to tap its prime location. Today, Batam hosts 31 industrial parks, three Special Economic Zones (SEZ), and thousands of manufacturing facilities producing everything from electronics to plastic packaging.

Once a hub for shipbuilding and manufacturing, Batam is now being recast as a regional digital powerhouse. Dozens of data centers are planned across the island, a place where water comes almost entirely from rainfall. But the rapid, and often unsustainable, expansion of these facilities is putting pressure on Batam’s limited water supply, raising concerns among residents who have long endured chronic water shortages.

In the midst of Batam’s water supply vulnerability, particularly during the dry season, the government has carved out a special economic zone (SEZ) in Nongsa dedicated to the digital industry. The area is home to animation studios, data center facilities, start-ups, and the long-delayed national data center project.

“Nine data centers are planned in Nongsa Digital Park, with four more coming soon,” said Irfan Syakir, Director of SEZ Development of the Batam Free Zone Authority (BP Batam).

“In total, around 18 facilities are in the pipeline.”

-Irfan Syakir (Director of SEZ Development)-

Not all of them are inside the SEZ. NeutraDC’s project, for instance, is being built in Kabil Industrial Park—mainly because, according to Indrama, “the infrastructure there was more ready than Nongsa’s.”

But even in Kabil Industrial Park, infrastructure remains fragile, underscoring a wider challenge that affects the entire island.

The NeutraDC–Nxera data center located in the Kabil Industrial Area. Once completed, the facility will require 3 million liters of water per day / NeutraDC–Nxera.

Data Center NeutraDC’s di Kabil Industrial Park. Jika proyek ini selesai, nantinya akan membutuhkan air 3 juta liter per hari untuk sistem pendinginnya/NeutraDC-Nxera

When Data Meets Drought

The availability of electricity is not a major concern; Batam’s grid still maintains a 37% reserve margin, though it remains largely powered by fossil-fuel plants. Water, however, is a far more precious and limited resource. Data centers rely heavily on water to cool their servers and prevent overheating that could shut down operations. Most facilities use fresh, treated water in their cooling towers because it transfers heat efficiently.

“Batam has no major river and little ground water to draw from,” Sudra Irawan, geomatics lecturer and researcher at Batam State Polytechnic, said to Katadata.

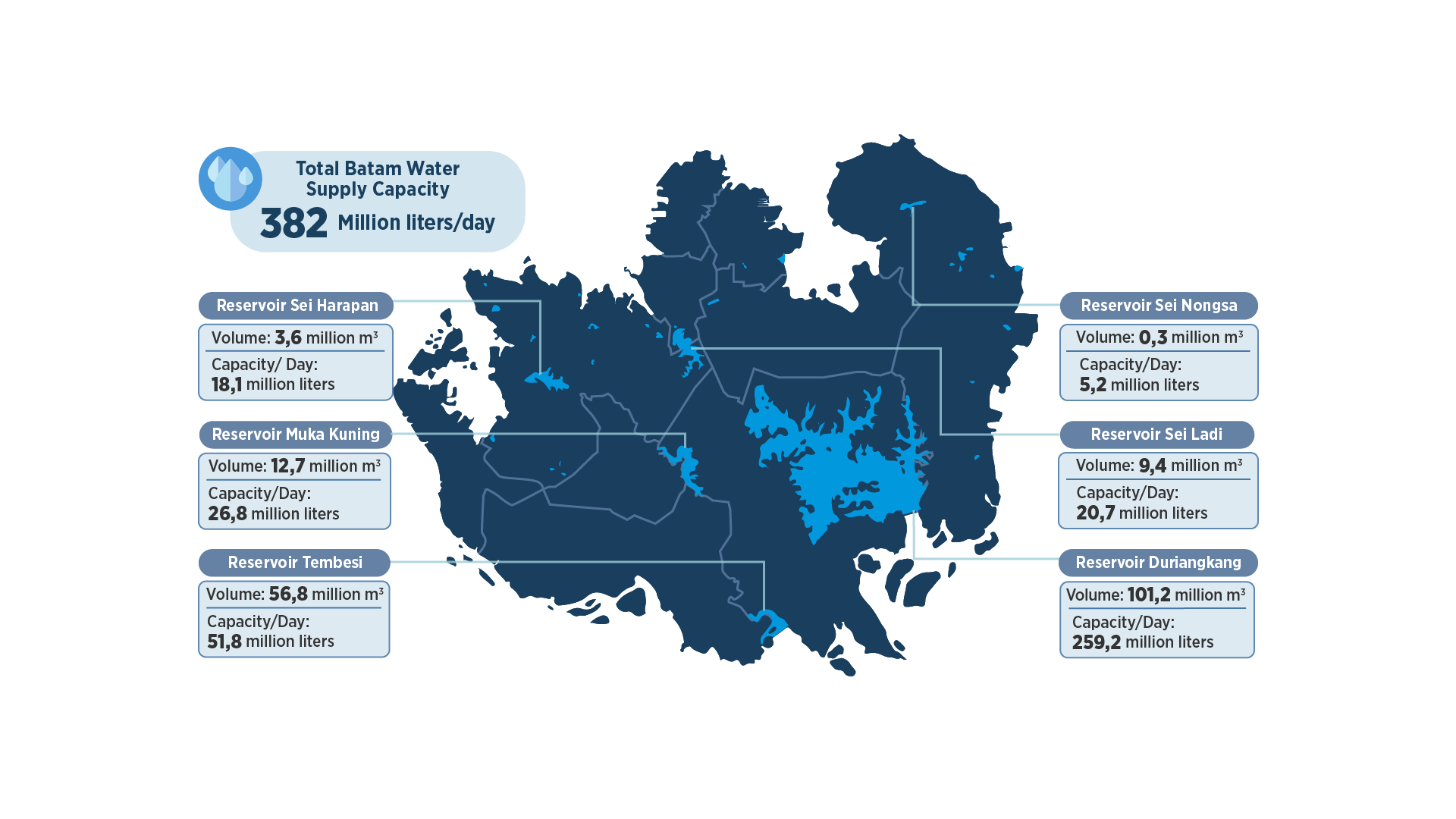

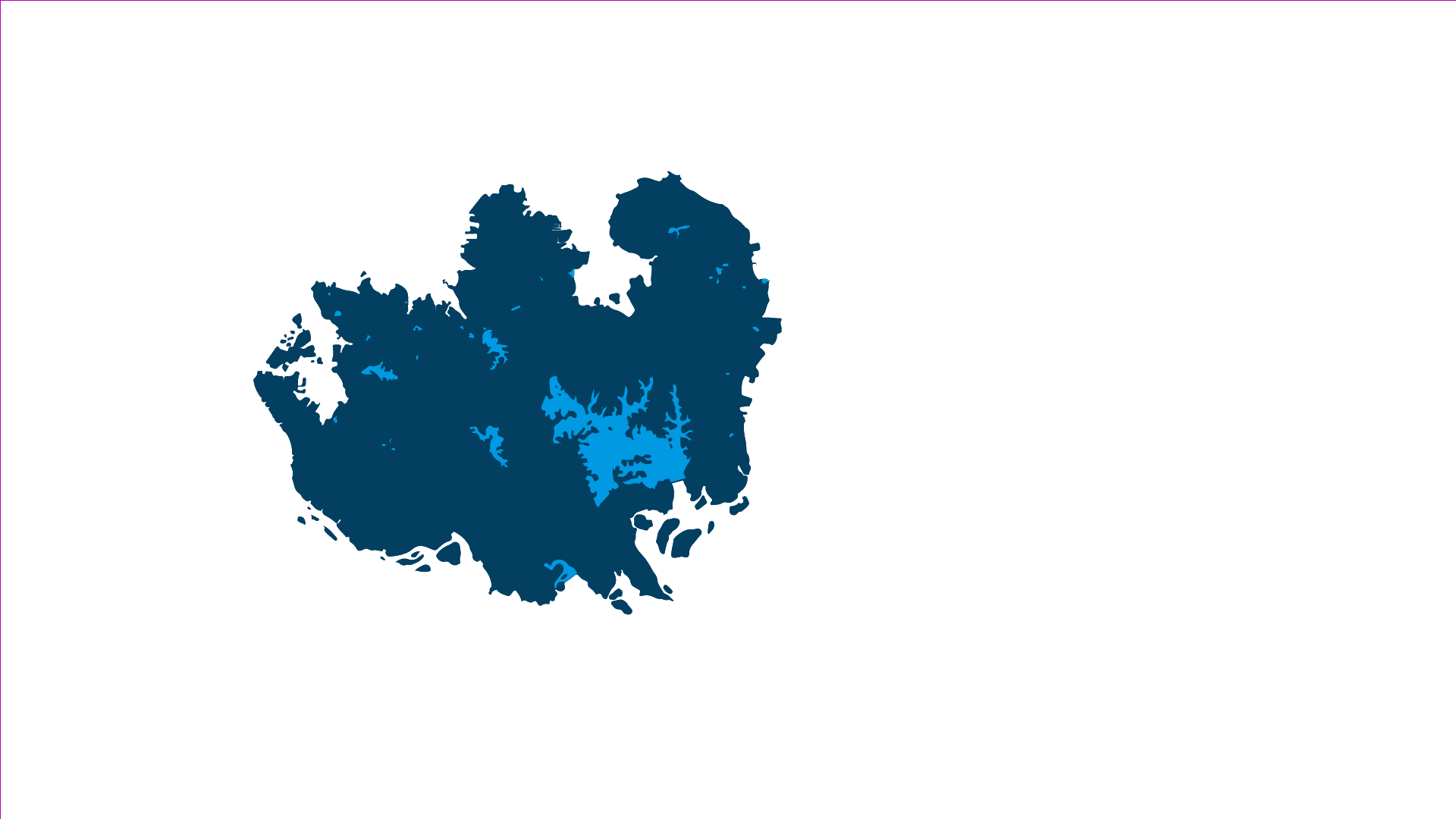

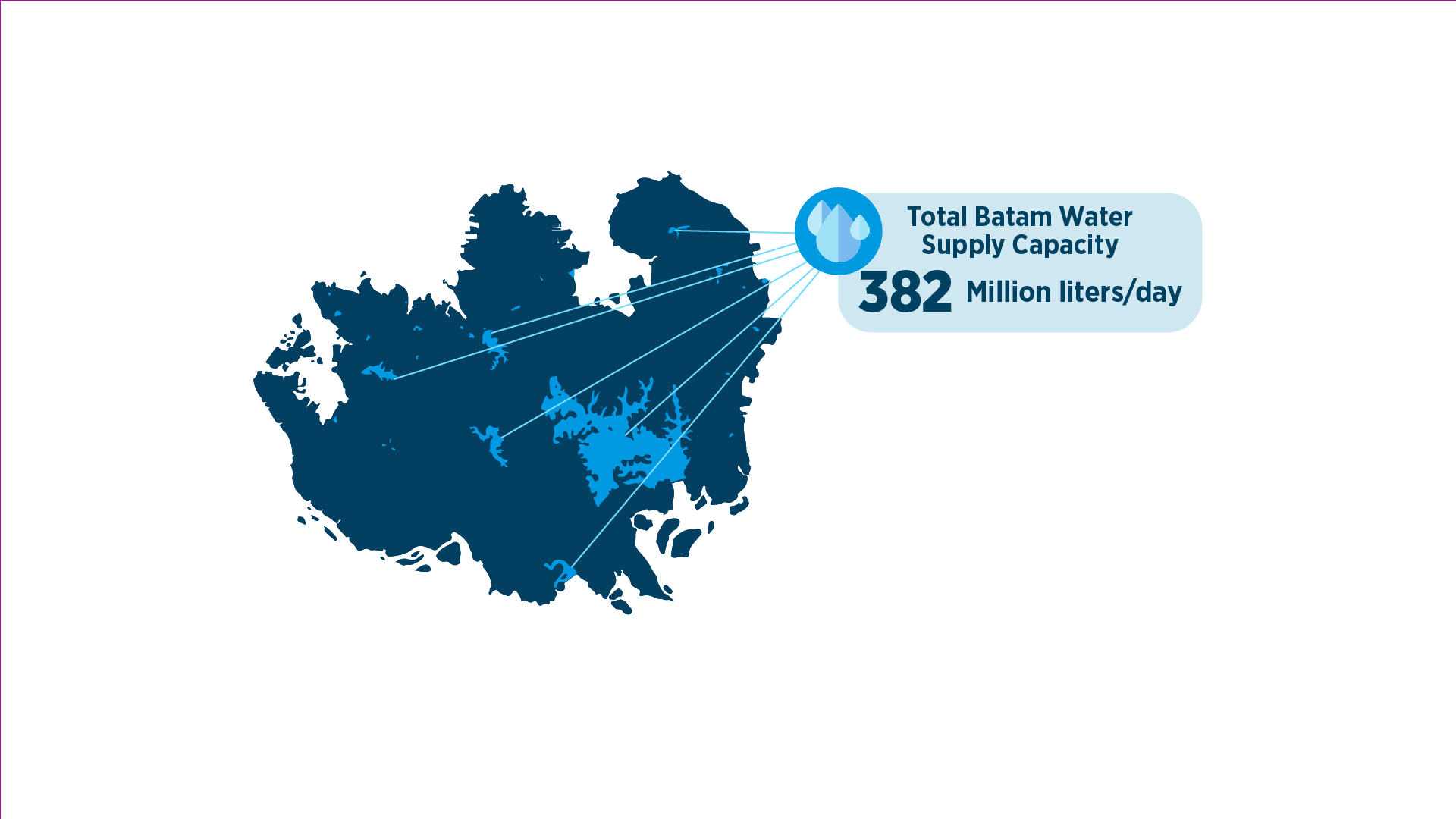

Groundwater wells have been permanently banned due to poor quality. The city now relies entirely on six rain-fed reservoirs, linked by a maze of pipes stretching across the island to the residents. It’s a fragile system: leaks, maintenance lapses, and dry spells often leave taps running dry. In some neighborhoods, residents get running water for only eight hours a day.

Muhammad Iwan (40), a resident of Teluk Mata Ikan—a small fishing village located just across from the Nongsa SEZ—still recalls the water crisis that struck his neighborhood in late 2024, which officials attributed to a leak in the piping system. For months, the taps ran only a couple of hours a day. To collect enough water, residents had to stay up late at night — the only time when the flow was strong.

“We couldn’t even perform ablution at the mosque because the water was only dripping,”

-Iwan (Resident of Teluk Mata Ikan)-

The situation lasted for about three months. Then, one day in mid-December 2024, dozens of villagers gathered in front of the data center facilities inside the Nongsa SEZ to protest. They were frustrated that water continued to flow steadily to the industrial area while their homes stayed dry.

Authorities blamed a “technical issue” in the piping system. And within days, the water returned to normal. According to Iwan, officials feared the problem might affect investor confidence, given the village’s close proximity to the SEZ.

“Since then, the water has run smoothly,” he said.

While Teluk Mata Ikan’s water supply has stabilized, many other areas across Batam continue to face chronic water shortages. Ariastuty Sirait, Deputy Chairman of Public Services at BP Batam, admitted that 18 “stress areas” currently experience limited water access.

“In higher lying areas, water only flows for two hours a day,” she said.

Fixing this will require massive investment — around Rp1.4 trillion (about US$85 million), according to BP Batam’s estimates. That’s nearly 74 percent of the authority’s annual budget.

“We asked the national government for funding,” Ariastuty said. “But the request was rejected.”

Although it is strategically located in the Strait of Malacca, Batam still faces challenges in its water supply.

There are currently 18 stressed areas in Batam. In these areas, water flows only for a few hours per day.

Meanwhile, Batam relies solely on six rain-fed reservoirs as its raw water sources.

While residents cope with water rationing, new digital facilities are preparing to draw millions of liters more. NeutraDC-Nxera’s 56-megawatt facility alone could consume around 3 million liters of water a day — roughly the equivalent of an Olympic-sized swimming pool — just to stay operational. That figure is nearly half of the Kabil Industrial Park’s current daily supply, which provides about 7.4 million liters of water daily to 45 companies spread across its 539 hectares.

“We’ve told Kabil our future needs,” Indrama of NeutraDC-Nxera, said.

The company insists its facility will be water-efficient. The third and fourth floors will use fan wall air cooling, while the second floor will employ direct-to-chip technology, circulating coolant directly to server processors to minimize evaporation loss.

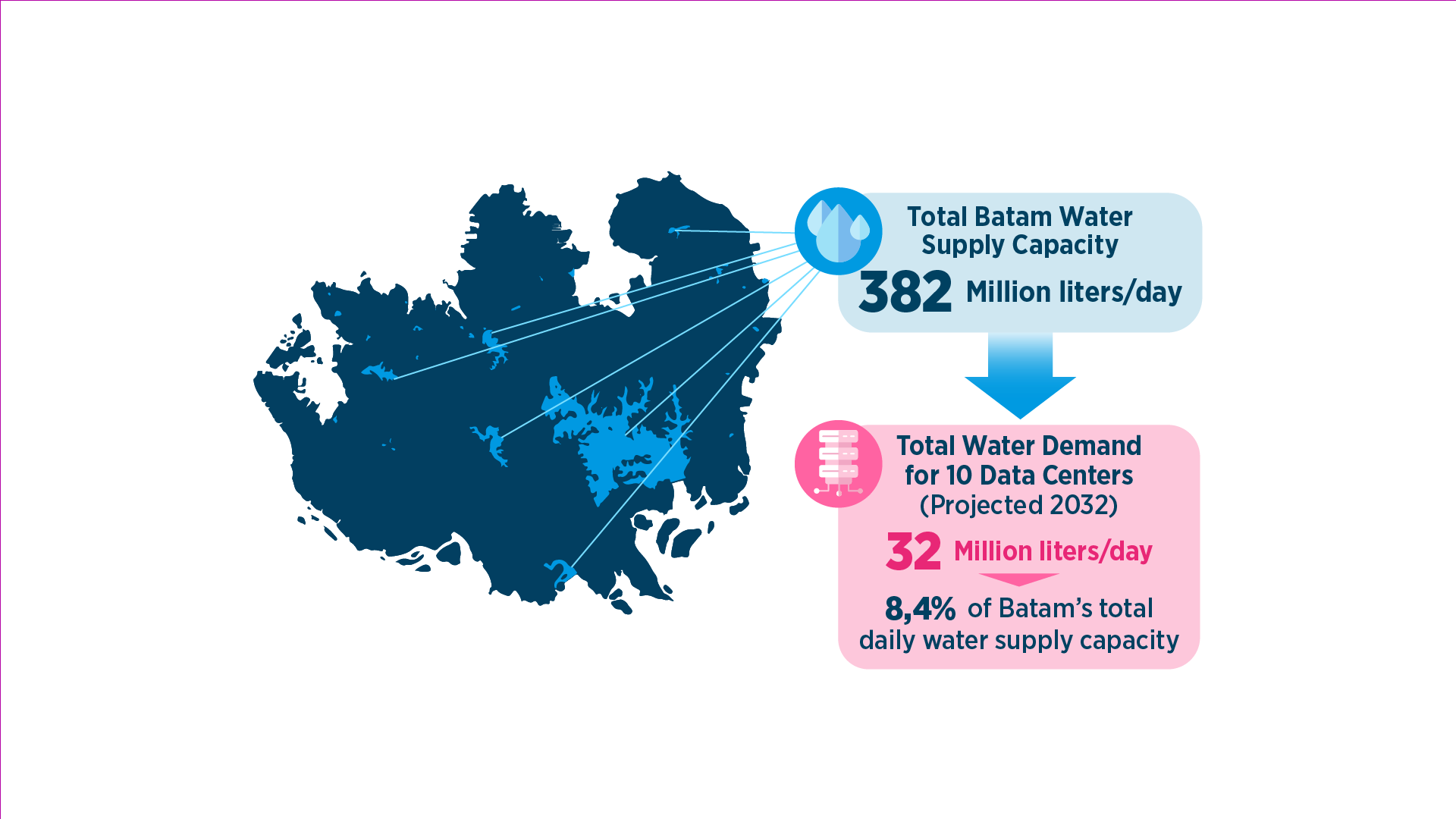

Still, the numbers are staggering. Data from BP Batam show that by 2032, the nine planned data centers in Nongsa Digital Park — with a combined IT load capacity of 285 megawatts — will require around 29 million liters of water per day. Add another 3 million liters for NeutraDC-Nxera’s facility, and together they would consume roughly 8.4 percent of Batam’s current total water supply.

“In the end, we will have to limit data center development. They consume too much water, while residents are still struggling to get enough,"

-Ariastuty (Deputy Chairman of Public Services at BP Batam)-

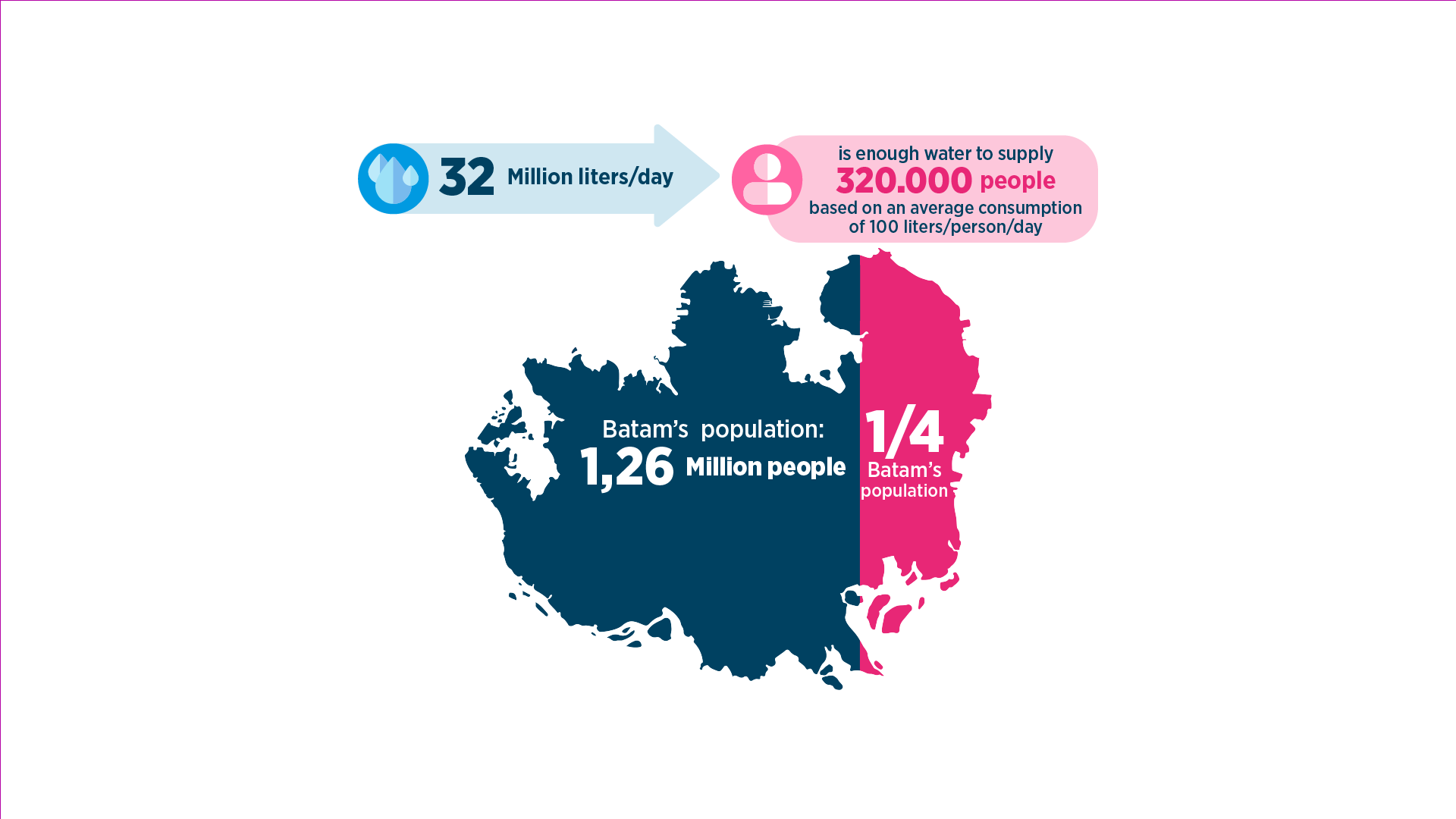

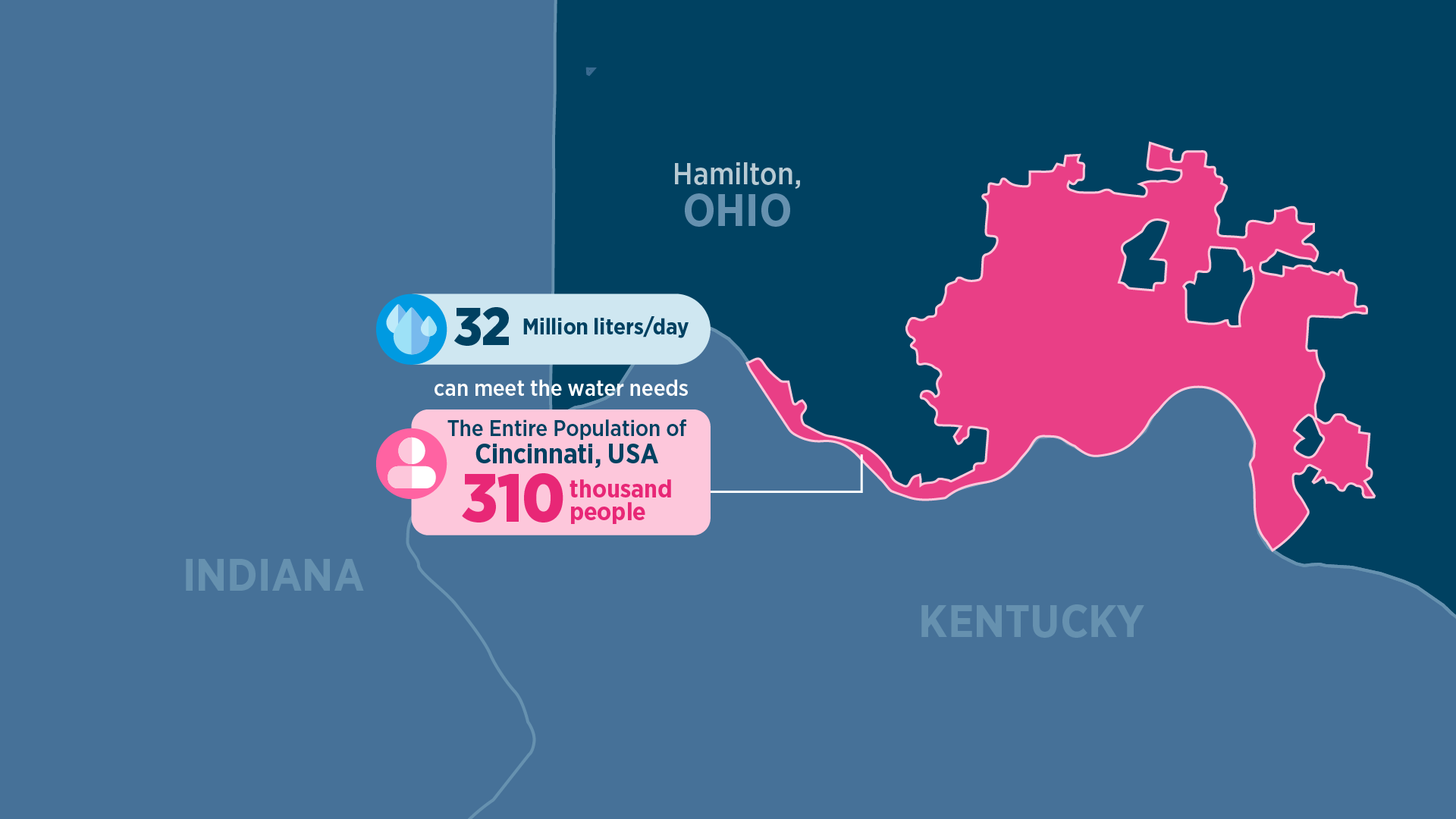

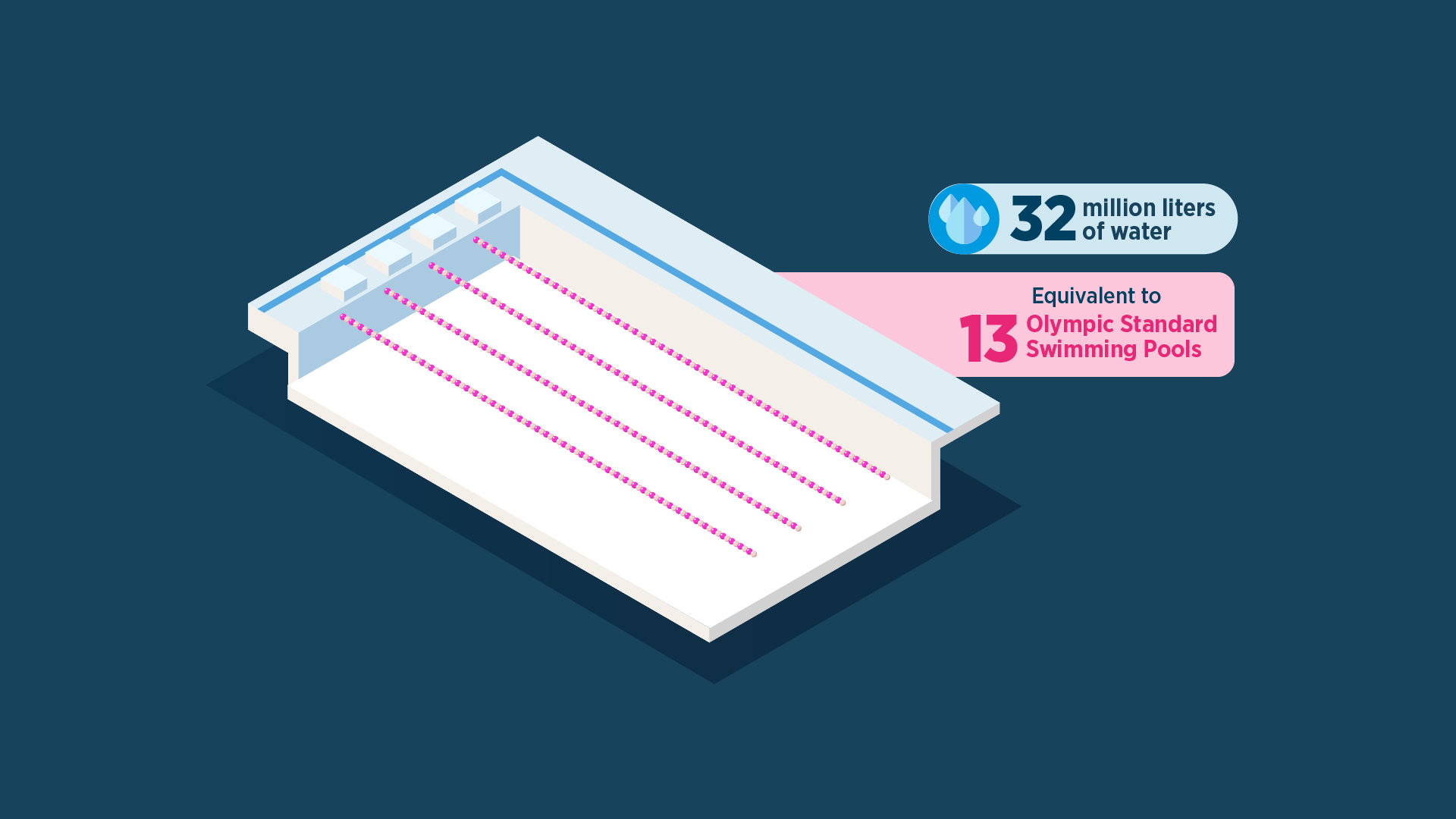

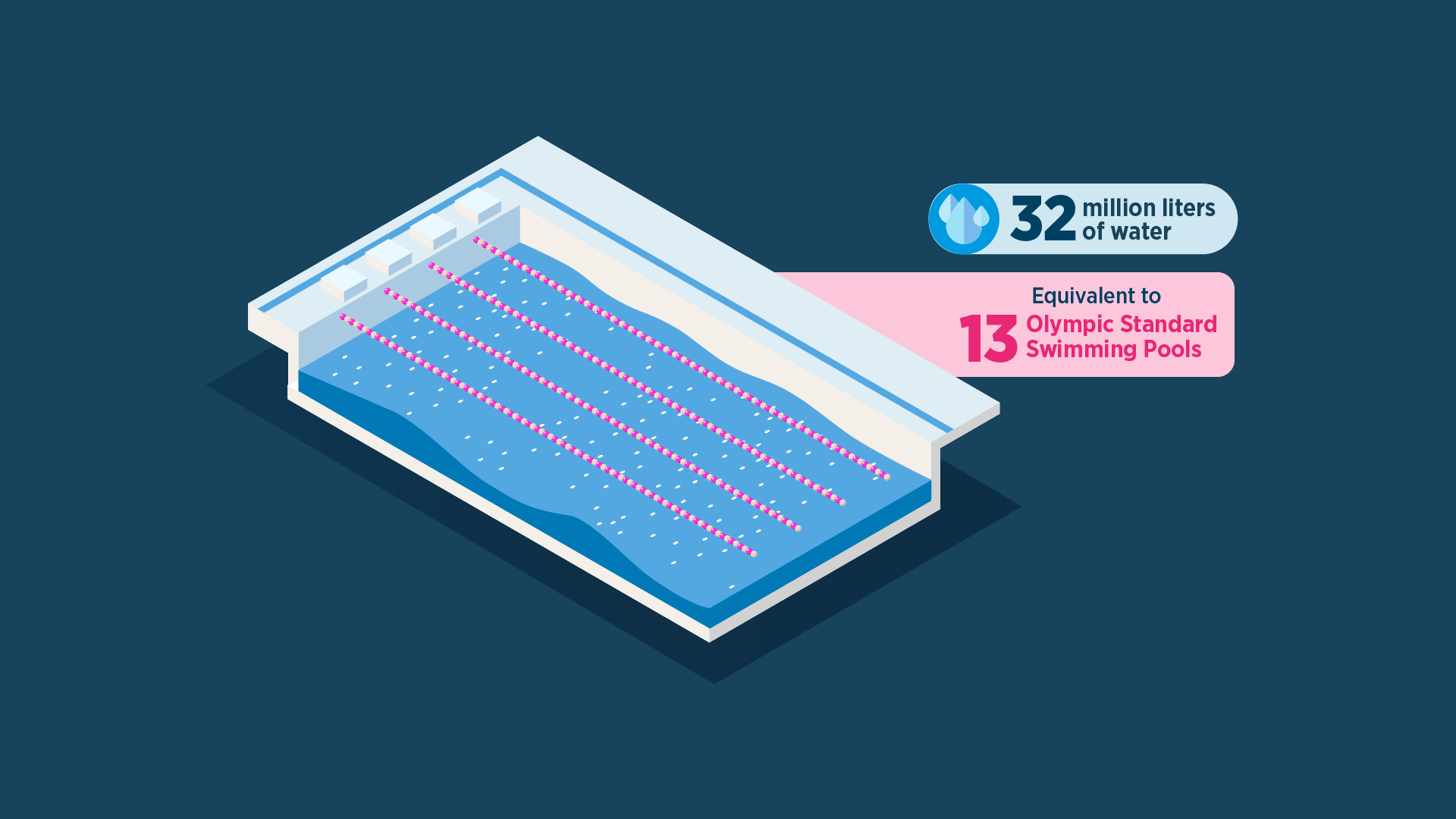

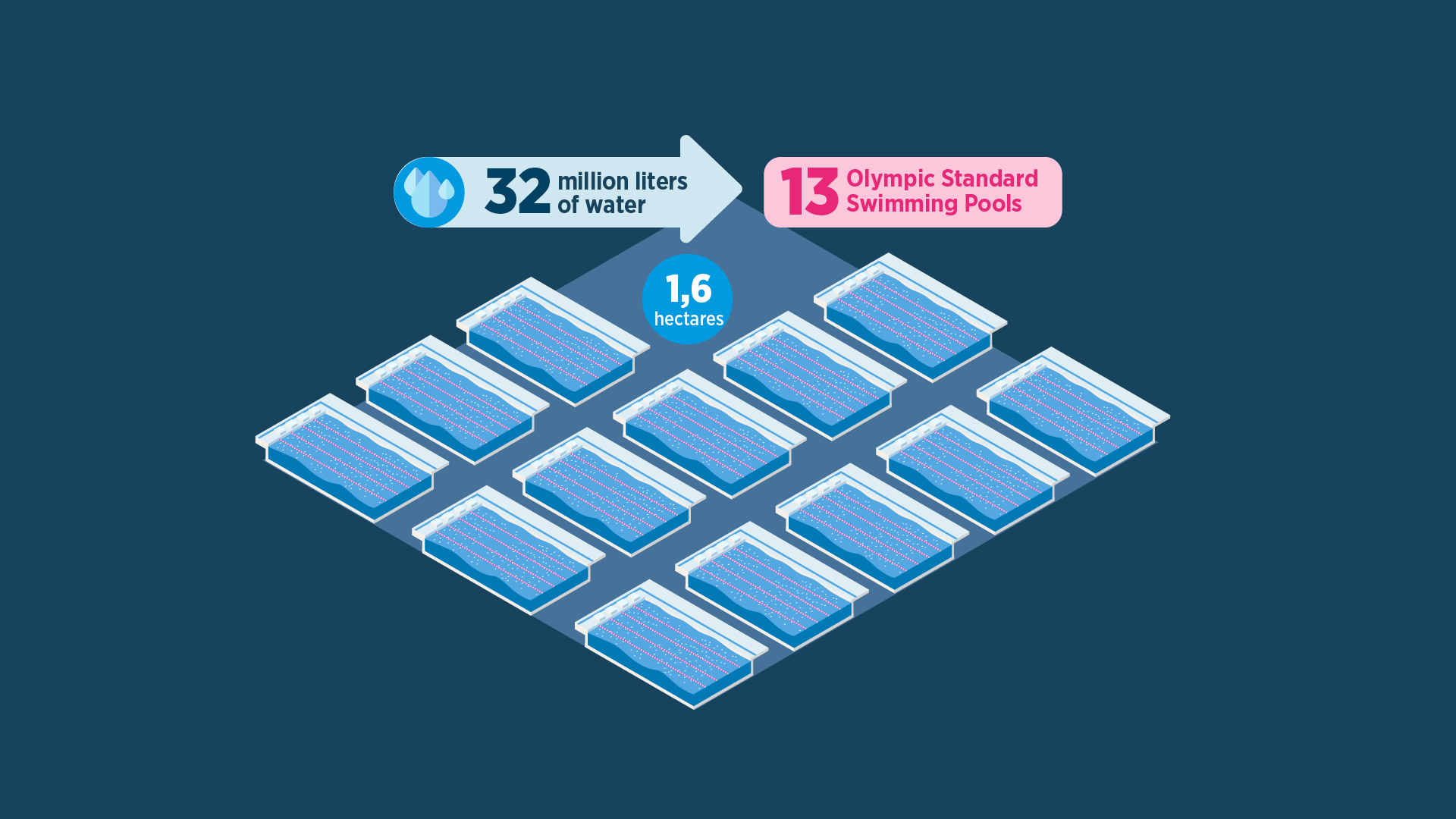

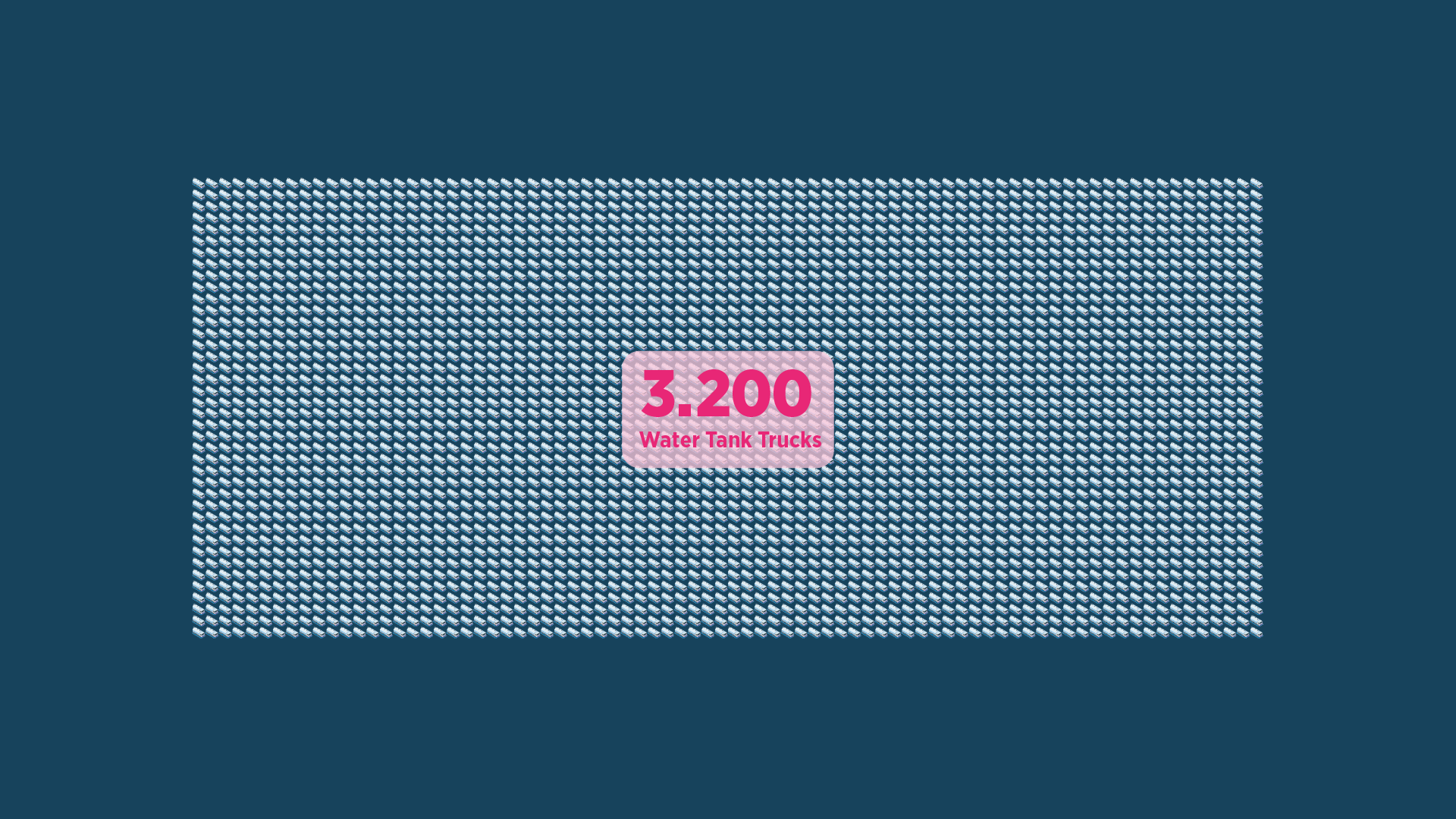

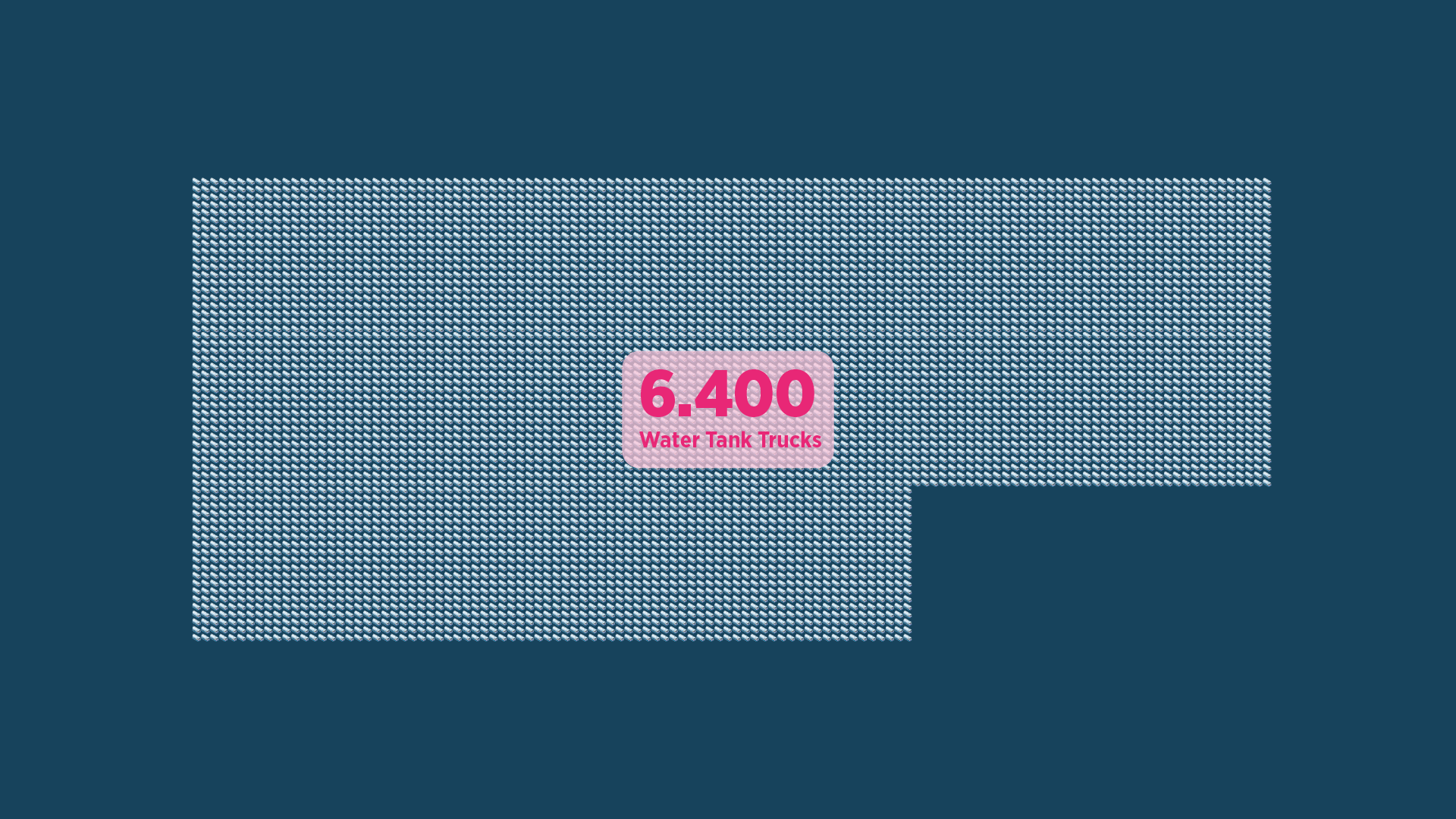

How much water do data centers in Batam need?

When operating at full capacity in 2032, the 10 data centers in Batam will require 32 million liters of water per day, or about 8.4% of the current total supply.

This amount could meet the needs of 320,000 people, or a quarter of Batam’s population.

This amount is also equivalent to the daily water needs of the entire population of Cincinnati, which reaches 310,000.

If all that water were used to fill Olympic-sized swimming pools, it would take 13 pools to hold it.

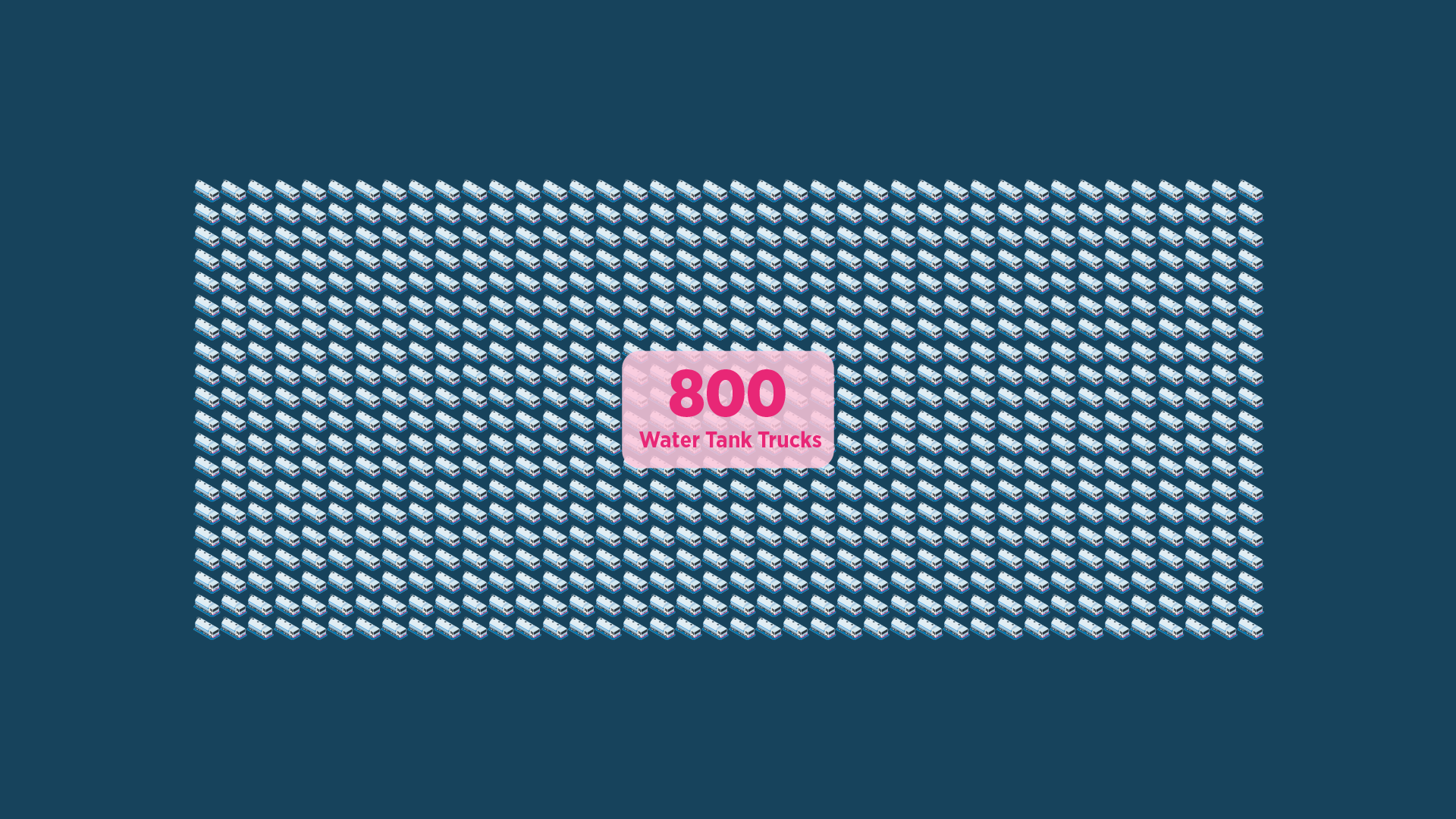

It would take 6,400 water tank trucks with a capacity of 5,000 liters each to supply 32 million liters of water per day.

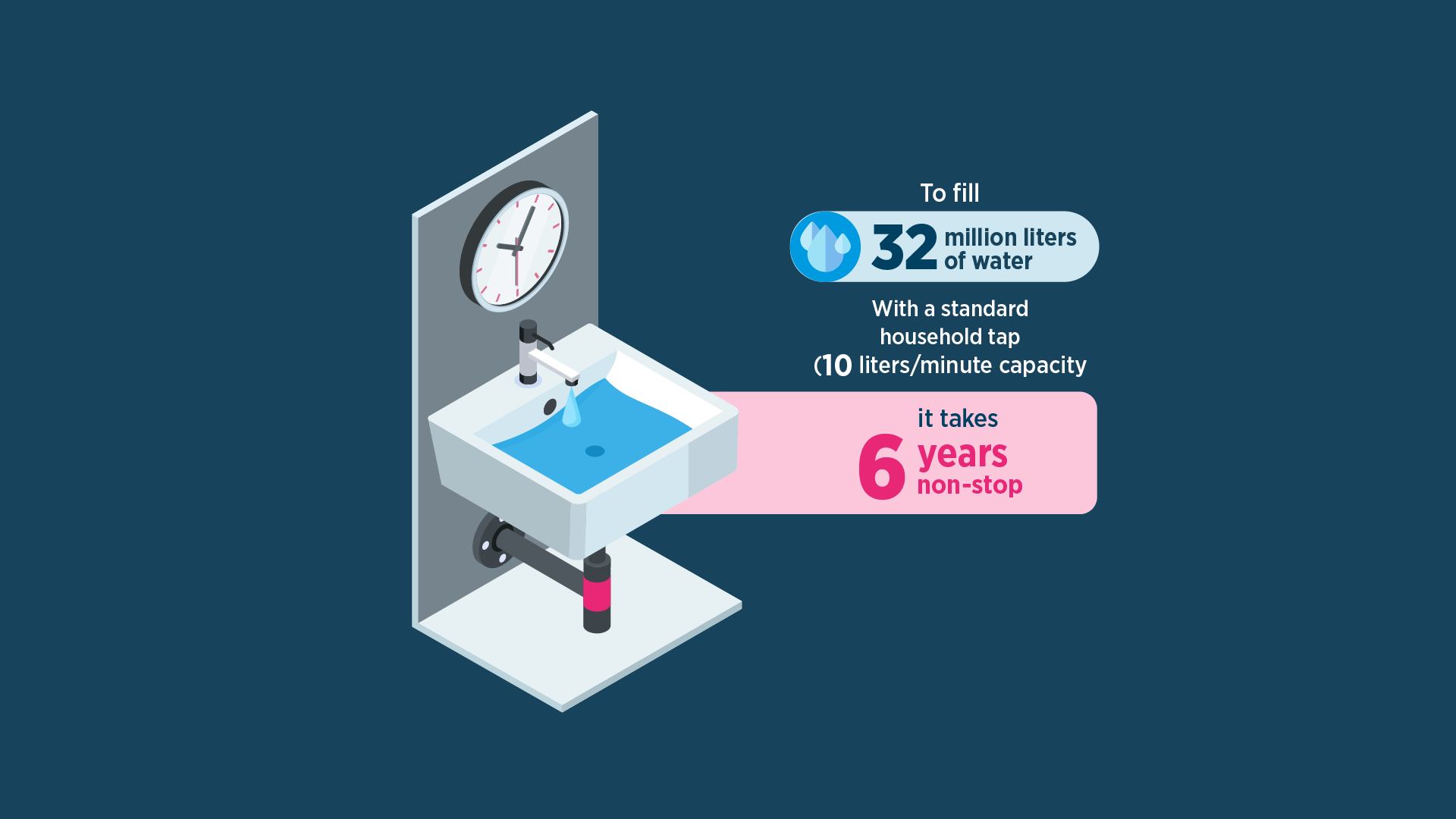

If using a household faucet, it would take 6 years of continuous flow to fill that amount.

City Living on rain

Batam’s vulnerability is not new. In 2020, the island endured months without rain. Reservoirs shrank, taps ran dry, and residents queued for water. The main reservoir — Duriangkang, which supplies 80 percent of Batam’s water — dropped 2.7 meters below its spillway. BP Batam even turned to cloud seeding to induce rain.

It was déja vu from 2015, when a similar drought crippled the city and residents were forced to buy drinking water just to bathe and even to collect it from puddles on the ground. “Batam depends entirely on its reservoirs,” said Hendrik Hermawan, Founder of Akar Bhumi, a local environmental NGO.

“But many of their catchment areas are already damaged.”

Six reservoirs currently supply about 382 million liters of water daily. For now, that’s just enough. But deforestation, pollution, and unregulated land use threaten their sustainability.

Around Tembesi Reservoir, residents have built fish cages and set up small farms—activities that are technically banned within 500 meters of any reservoir.

“Runoff from livestock waste and pesticides is contaminating the reservoirs. We’re working to fix this,” said Ariastuty.

Batam’s history of water management has long been troubled. The city lost one of its vital water sources after years of land squatting around the Baloi Dam. Built in 1977, the reservoir endured decades of informal settlements that severely contaminated its water with heavy metals, like cadmium, chromium, and lead, as well as chemical detergents. By 2012, authorities had no choice but to shut down the dam. Since then, the once-pristine reservoir has deteriorated into what locals grimly describe as a giant septic tank.

Hendrik Hermawan of Akar Bhumi called the Baloi Reservoir case a “tragedy.” He urged authorities to pay closer attention to the health of the remaining reservoir ecosystems to prevent history from repeating itself.

“It’s such a shame that we lost the Baloi Dam,”

-Hendrik Hermawan (Akar Bhumi Activist)-

Ariastuty, on the other hand, remains hopeful about the future of the Baloi Dam. She acknowledges that authorities would need to displace thousands of people living around the reservoir to make it operational again. Batam needs every drop of water it can get and the Baloi Dam is no exception.

“We haven’t lost hope. We’ll figure it out,” she insisted.

Batam, however, has an infamous history of relocating its inhabitants for infrastructure projects. On September 7, 2023, a clash erupted between thousands of armed personnel—including military forces and police—and residents of Rempang, an island under Batam’s administration. The tragedy was triggered by the government’s plan to build an industrial zone, including a solar panel factory, which would displace thousands of Rempang residents.

Hermawan of Akar Bhumi described the incident as one of the darkest human rights records in Batam. He warned that relocating people living around Baloi Dam would pose a major challenge, as many have lived there for years.

“Now thousands of people live around Baloi Dam. How will BP Batam relocate them?” he said.

The water quality of the Baloi reservoir is contaminated by cadmium, chromium, lead, and detergents / Katadata.

The water quality of the Baloi reservoir is contaminated by cadmium, chromium, lead, and detergents / Katadata.

The Baloi reservoir, built in 1977, has no longer been usable as a raw water source since 2012 / Katadata.

The Baloi reservoir, built in 1977, has no longer been usable as a raw water source since 2012 / Katadata.

Illegal settlements have spread around the Baloi reservoir / Katadata.

Illegal settlements have spread around the Baloi reservoir / Katadata.

Agricultural activities around the Tembesi reservoir threaten Batam’s water source ecosystem / Katadata.

Agricultural activities around the Tembesi reservoir threaten Batam’s water source ecosystem / Katadata.

Water pipes for agricultural use at the Tembesi reservoir / Katadata.

Water pipes for agricultural use at the Tembesi reservoir / Katadata.

Pesticides and chemicals from agricultural activities contaminate the water of the Tembesi reservoir / Katadata.

Pesticides and chemicals from agricultural activities contaminate the water of the Tembesi reservoir / Katadata.

Pumps channel water from Tembesi with a capacity of up to 51 million liters per day / Katadata.

Pumps channel water from Tembesi with a capacity of up to 51 million liters per day / Katadata.

Singapore’s satellite city

Amid the surge of digital infrastructure investment, Batam is grappling with a major water management challenge. According to Sudra Irawan of the Batam Polytechnic, beyond pollution and contamination, the city’s growing population and expanding industries have also driven up water demand. Today, Batam is home to around 1.26 million people — a number projected to keep rising, fueled by both high birth rates and migration.

“A prolonged dry season in the future, which could further reduce reservoir levels, still looms over Batam,”

-Sudra Irawan (Researcher of Batam Polytechnic)-

Batam is one of Indonesia’s most unique cities — a place built almost entirely from scratch. Once blanketed by dense forest, Batam was virtually an unpopulated island before the 1970s, home to only a handful of fishermen living along its coastal areas. Under the directive of President Soeharto’s military regime, the island was cleared of forests in the 1970s to make way for industrial development.

Once the island was cleared and began to grow as an industrial city, it became clear that Batam needed a stable water supply. The government then initiated the construction of several reservoirs to meet the city’s increasing water demand. The Baloi Dam was the first to become operational in 1978, followed by the Sei Harapan Dam in 1979, with additional reservoirs built in the subsequent years.

Batam soon transformed into a thriving industrial hub and became a key part of the SIJORI Growth Triangle, a subregional economic cooperation linking Singapore, Johor (Malaysia), and Riau (Indonesia). Over the decades, this partnership turned Batam into an industrial satellite city for Singapore. The island hosts factories, shipyards, and electronics assembly lines. Now, in the digital era, the same logic drives the data center boom.

Singapore, for its part, imposed a temporary pause on new data center developments in 2019, facing both energy and land constraints. The moratorium was lifted in 2022, but only with the introduction of strict sustainability and efficiency requirements for future projects. Since then, many investors have looked across the strait to Johor and Batam, where land and resources remain more accessible for data center expansion with minimal regard for this infrastructure’s other primary need: water.

Johor has been a step ahead of Batam in attracting data center investors. According to a Malaysiakini report, the Malaysian state has drawn 72 data center projects, with at least 13 already operational and a projected total capacity of 2.6 gigawatts by 2027. The boom has raised concerns over Johor’s water and energy supply, while across the strait, Batam is eager to seize the spillover opportunity from the growing regional demand for data infrastructure.

Nicholas Toh, Managing Director and Head of Data Centre Platform, Asia at Gaw Capital Partners — the firm behind Golden Digital Gateway’s 5.2-MW facility in Nongsa — said Batam’s tax incentives under the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) give it a competitive edge over other emerging data center locations.

“Our view is that it’s not a question of if Batam will blossom. It’s a question of when,”

-Nicholas Toh (Managing Director Gaw Capital Partners)-

He added that the facility’s cooling system design prioritizes air-based methods over water-intensive systems. The infrastructure is also built with flexibility for future upgrades, as AI workloads may eventually require liquid cooling technology.

Still, the overall water demand from large-scale data centers — even those using more efficient systems — remains a pressing issue on the island, where most reservoirs depend entirely on rainfall. By 2032, the 5.2-MW Golden Digital Gateway facility is projected to require around 881,000 liters of water per day.

Nevertheless, the growing demand for water from data centers has raised concerns among residents. Ishlahudin (30), who has lived in Batam for most of his life, warned about the city’s vulnerability to dry spells such as those that occurred in 2015 and 2025. He fears that the water needs of data centers will be prioritized over those of citizens, especially during prolonged droughts.

“Data centers must find adequate water sources. Don’t sacrifice the reservoirs meant for the people,”

-Nicholas Toh (Managing Director Gaw Capital Partners)-

BP Batam is exploring several solutions to address this issue. Irfan Syakir explained that, specifically in the Nongsa Special Economic Zone (SEZ), the authority plans to build a water treatment facility with a capacity of 30 million liters per day to meet the needs of the digital industry. “That’s the advantage of investing in the SEZ,” said Irfan Syakir. “We are fully committed to supporting the industry.”

Meanwhile, Ariastuty also encouraged data center companies to help find solutions for water supply, one of which is by considering seawater desalination technology. “There’s already a company in Batam that produces it,” said Ariastuty.

She acknowledged, however, that the technology still faces challenges related to investment and cost. For comparison, the price of industrial water in Batam is around Rp12,000 (US$0.72) per cubic meter, while desalinated seawater can cost between Rp28,000 (US$1.69) and Rp36,000 (US$2.17) per cubic meter. In addition, the initial investment remains high. According to BP Batam’s calculations, a facility with a capacity of 300 cubic meters could cost up to Rp300 billion (approximately US$18.1 million).

“Desalinated water is still expensive,” said Indrama from NeutraDC-Nxera. “In the end, it will depend on client demand,” he added.

As data center demand continues to grow across the region, Batam’s strategic location — coupled with its various incentives — is likely to make the island one of investors’ favorite destinations. Yet, its vulnerability remains.

“If a dry spell hits Batam again, who will be prioritized — the data centers or the residents?”

-Hendrik Hermawan (Akar Bhumi Activist)-

This report is part of “Dark Side of The Boom”, a collaborative project involving 14 media outlets across Asia, initiated by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Writer: Rezza Aji Pratama

Visual Journalist: Antonieta Amosella, Bintan Insani

Data Journalist: Puja Pratama Ridwan

Editor: Hari Hidowati

Development: Firman Firdaus & Puja Pratama Ridwan