Tsunami, a Reprimand for Govt to Improve Early Warning System

BMKG actually has a tsunami early warning system named InaTEWS, which was launched in 2009. This system combines seismic data, Global Positioning System (GPS), Buoy and Tide Gauge. The problem is that not all of the data can be obtained due to limited infrastructure.

BMKG has 263 seismic stations to detect earthquakes in Indonesia. Its equipment can also detect potential tsunamis within five minutes after an earthquake occurs. The high number of stations makes the seismograph data as the main reference in tsunami monitoring. Ideally, all data in InaTEWS can be utilized.

Basically, seismic data alone is not accurate enough to detect potential tsunamis. Additional data is required, one of them is from the GPS station. Its equipment, with the help of satellites, can measure the shift in the surface of the earth caused by earthquakes. Currently, Indonesia only has seven GPS stations.

In detecting tsunamis, buoys can be used to obtain accurate data. The floating device can quickly detect the pressure of waves on the seabed. The height of the waves that will hit the coast can also be detected accurately. If it has the potential to cause a tsunami, an early warning alarm can be activated.

The problem is that there are only 27 units of buoy devices in Indonesia, most of which are donations from other countries after the 2004 Aceh Tsunami. Germany gave 10 units, Malaysia one unit, and the US two units. Meanwhile, the government made eight units. Since 2012, 22 of these devices have ceased to function. Only five units of the buoy can still be used, but these devices do not belong to Indonesia. One unit (belonging to India) in Aceh, one unit (Thailand) in the Andaman Sea, two units (Australia) in Sumba and one unit (US) in Papua.

The government needs to allocate funds to fix all those devices. One buoy device costs Rp 7.8 billion. It costs only Rp 4 billion if it is all locally made. “We need 25 units, which means around Rp 100 billion. It is not too big to oversee the entire territory of Indonesia. The tighter the network, the better,” Sutopo said during a press conference at Graha BNPB, Jakarta, Wednesday (12/26).

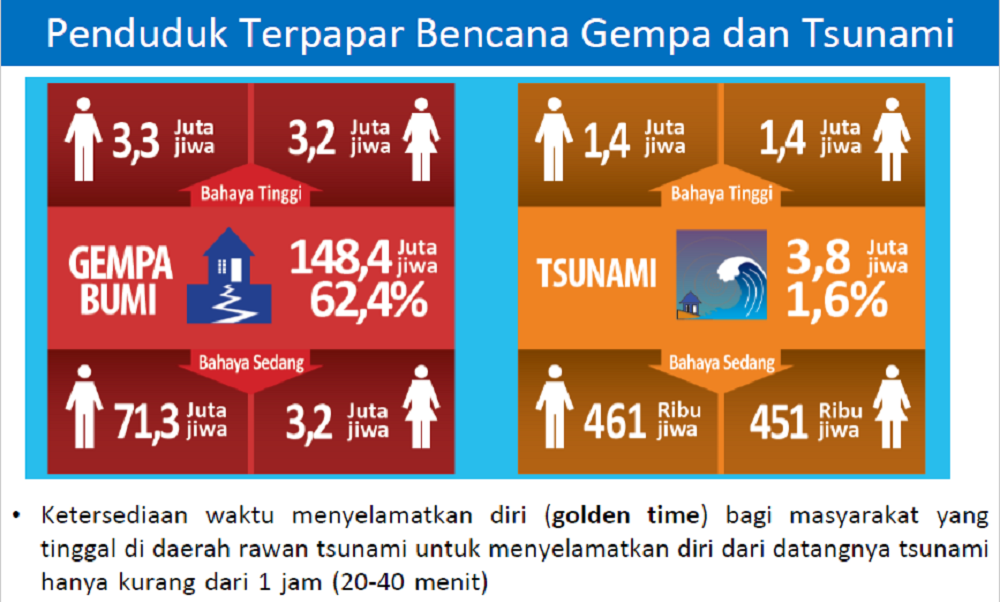

Indonesia's territory, which is mostly oceanic and prone to disasters, also requires many tsunami warning sirens. Currently, there are only 52 sirens throughout the country. According to Sutopo, Indonesia requires at least 1,000 units of sirens, meaning it still needs another 948 units.

So far, the Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology (BPPT) is the party responsible for the procurement and maintenance of buoys. BPPT Deputy of Technology for Natural Resources Development Hammam Riza previously said the government needs to allocate more funds if it wants to re-operate the buoy devices.

According to him, the cost of procuring 25 buoys is Rp 150 billion, while the maintenance costs reach Rp 30 billion per year. This means the budget needed for the buoy management is equivalent to 12 percent from the total of BPPT’s budget of Rp 1.47 trillion in 2017.

Compared to the total expenditure of the central government at Rp 1,454.5 trillion this year, the budget for buoys is only 0.012 percent. This is quite small considering the importance of optimising the tsunami early detection capability to save the lives of many people.

The government seems late in responding to this weak disaster prevention system. After the tsunamis in Banten and Lampung, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) realized that improvements are necessary. He then instructed the BMKG to immediately purchase tsunami early detection equipment.

“I have ordered BMKG to buy equipment that can provide early warnings,” Jokowi said when visiting the disaster site in Carita Subdistrict in Pandeglang Regency, Banten, Monday (12/24).

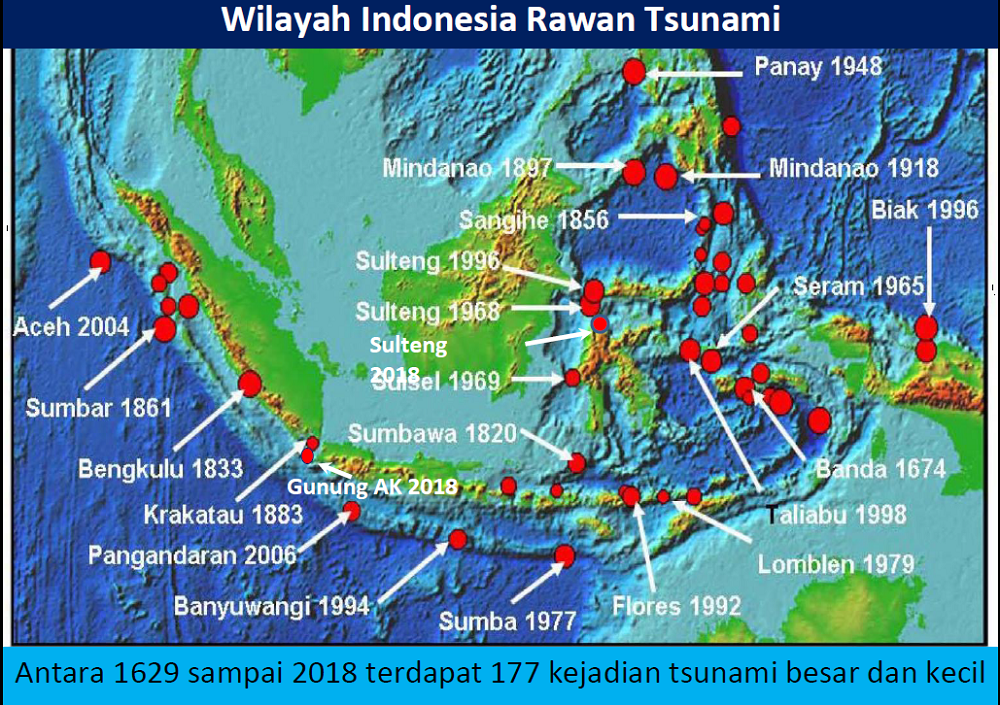

The Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) stated that Indonesia still has a low level of disaster preparedness. Human Ecology Researcher Deny Hidayati said disaster awareness at the regional level did not meet preparedness parameters. Concern increased after major disasters, such as the tsunami in Aceh and the earthquakes in Lombok and Palu, but this was later forgotten.

“Concern should be increased again by emphasizing that we are indeed in disaster-prone areas. We must be prepared,” Deny told Katadata.co.id in an interview at LIPI headquarters in South Jakarta, Thursday (12/27).